CASE STUDY

Bottlenecks and Opportunities Around the Use of Maternity Waiting Homes in Malawi

Prevention, detection, and management of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) in Malawi

Malawi has had maternity waiting homes (MWHs) for the last two decades. They are residential accommodation facilities located close to a health facility where expectant women can wait until they go into labor. MWHs are considered to be a key element of a strategy to "bridge the geographical gap" in obstetric care between rural areas, with poor access to equipped facilities, and urban areas where the services are available. They have the potential to improve maternal newborn health (MNH) outcomes, although additional evidence regarding their use is warranted. There is poor documentation of the number, characteristics, and experiences of women who use MWHs.

Even though about 90 percent of deliveries in Malawi were taking place at a facility with a skilled provider, only 42 percent received a check-up within 48 hours of childbirth. MWHs was considered to be potentially helpful in improving PPH outcomes by offering them a residential facility for high-risk women to stay post-delivery before traveling home and as a means of providing family members of women with information on warning signs for PPH and other MNH issues before birth, as recommended by the Ministry of Health and Population (MoH).

A study was conducted under a larger research work led by Advancing Postpartum Hemorrhage Care (APPHC) Partnership on prevention, detection, and management of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) which continues to be the biggest threat to childbearing women in Malawi. As part of the study, the team undertook scoping activities, stakeholder consultations, and a formative assessment between April 2019 and March 2020. The objective was to understand the key implementation barriers, bottlenecks, and opportunities for improved prevention, early detection, and treatment of PPH in Malawi.

The mixed-method study was conducted in 25 facilities in the districts of Lilongwe, Balaka, Zomba, and Dowa. The team conducted exit interviews with postnatal women aged 15 years and older (n=660) to understand their experiences with MWHs prior to giving birth at a study facility. This was accompanied by in-depth interviews (IDIs) with postnatal women and maternal health providers to examine their perceptions on MWHs, barriers, and facilitators for use, and opportunities to improve uptake.

Findings are categorized into the usage of MWHs, attendance by health providers, duration of stay, and provider and postnatal women’s perceptions of MWHs, cost of staying in an MWH, availability of space, and provider attitudes.

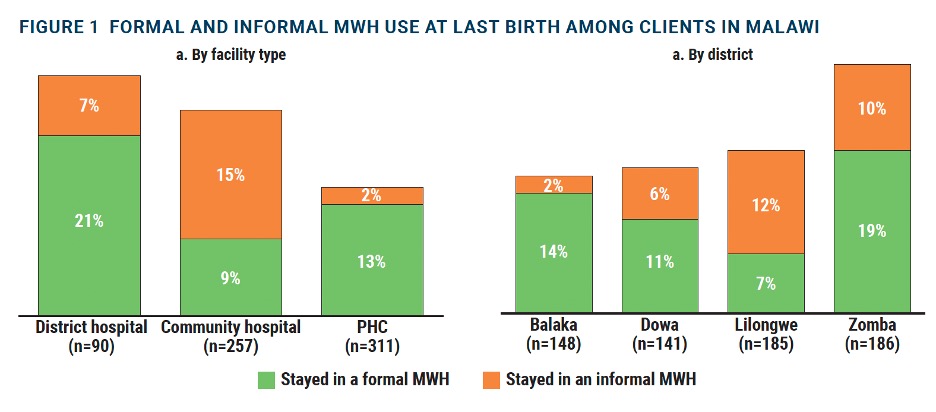

Use of formal and informal MWHs among pregnant women in Malawi

As shown in Figure below, 21 percent of postnatal women interviewed reported staying in or near the hospital before giving birth, 13 percent at a formal MWH, and 8 percent at an informal structure. Women who delivered at district hospitals were more likely to stay at an MWH (28%, p=0.004) and in particular at a formal MWH (21%). By district, significantly more women stayed at an MWH in Zomba (29%, p= 0.006). In terms of the use of MWHs by women’s characteris¬tics, there were no significant differences in the use of MWHs by a number of previous births (parity), age, marital status, education, or ANC visits. However, those who lived within 30 minutes of a facility were less likely to stay at an MWH (4%) than those who traveled between 30 and 55 minutes (21%) or an hour or more to the facility (23%), and this difference was significant (p=0.002, data not shown).

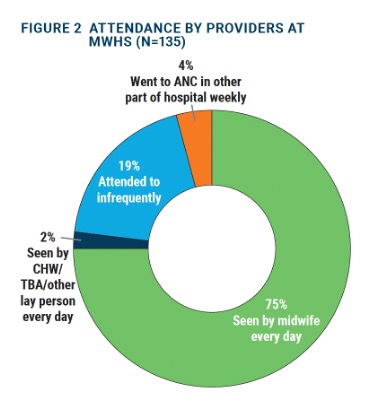

Attendance by health care providers during MWH stay

Of those women staying at an MWH, approximately 75 percent of women said they were visited by a midwife every day (see Figure below), where the expectation is that women who are stable are seen at least two or three times a week, and women with a risk factor are seen at least once every day for monitoring. There were no significant differences by facility type (p=0.064), though attendance did differ by district (p=0.044), with those in Lilongwe most likely to be visited by a midwife every day (83%).

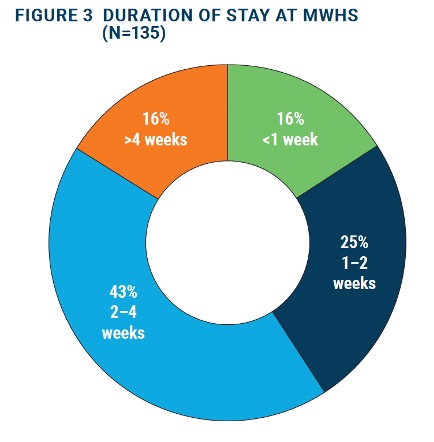

Duration of stay at an MWH

Nearly 68 percent of respondents stayed at an MWH between 1-4 weeks (see Figure 3 below), though there were no significant differences by facility type (p=0.319) or district (p=0.651) in the duration of stay. Provider and postnatal women’s perceptions of MWHs Below is a summary of findings from the qualitative interviews that offers insights on the facilitating and constraining factors for utilization of MWHs by women.

Costs of staying in an MWH

Some beneficiaries reported that while there were service fees to stay at the MWHs, they did have to cover the costs of both transport to the MWH and food while staying there.

“[The cost] depends on the village of your origin. Some pay, but for us, the government takes care of that…. The food was scarce due to the lack of money.” —IDI, Postnatal woman

Providers also corroborated that cost was a prohibiting factor for women staying in MWHs.

"They pay nothing. They don’t pay anything, but they would. But that is a challenge and as I said they stay with a guardian in the same place, they eat hospital food but the guardian needs food so can’t stay here with no money. – IDI, Provider

Availability of space in MWH

Providers also felt that space was a constraint in MWHs and the maternity unit, especially informal maternity units as evidenced by the quote below:

“It would be better if it was a special place…. It’s the same room with few beds for postnatal mothers and a few beds for antenatal mothers waiting...sometimes some women may come for waiting but when the room is full they are told to go back.” – IDI, Provider

Women also echoed similar challenges at MWHs including physical constraints. Few women mentioned inadequate conditions and being asked to do chores by hospital workers at MWHs.

“I found myself at the maternity waiting home because I had malaria in pregnancy…. The space for sleeping was not adequate. We were woken up early in the morning because they wanted to mop the room. They will wake us up to do chores in the morning…like hospital workers. Hygienically it was not good especially in the bathrooms.” --- IDI, Postnatal women

Provider attitudes

Health providers reported that client perceptions of provider attitudes were an impediment to optimal use of MWHs, especially their tone of voice and provision of mixed advice that could have confused the clients.

“Attitudes for some of the providers: this is also another factor because some providers have got their voices which is very loud…. [The providers] may say ‘hey I told you to go and ambulate’ and [the clients] may feel like maybe I should come when the labor is well established. As a result, they come in the second stage of labor or some may just opt to say ‘oh I just go there with a baby”. – IDI, Provider